For 62 years, veterans of the Civilian Conservation Corps, most of them from Company 556, have been coming to Indiana’s Pokagon State Park on the last Sunday in July, for the oldest continuous CCC reunion in the country. For the last 25 years, I have never missed one, although the rapidly dwindling number of veterans is painful to see.

For 62 years, veterans of the Civilian Conservation Corps, most of them from Company 556, have been coming to Indiana’s Pokagon State Park on the last Sunday in July, for the oldest continuous CCC reunion in the country. For the last 25 years, I have never missed one, although the rapidly dwindling number of veterans is painful to see.

In 1953, twenty years after the CCC had been established in the depths of the Depression, Roger Woodcock, formerly of CCC Company 556, along with several others who had worked at Pokagon, sought the park’s help in setting up a reunion. The gathering would be at the open air Combination Shelter overlooking the beach, both constructed by Company 556. Roger consulted a local meteorologist as to the best day to hold the event, and the fellow assured him that it never rains the last Sunday in July. Indeed, in all those years, it has rained only four times.

Pokagon State Park was largely unforested farmland when the Indiana Department of Conservation took possession in 1925 and named it to honor Simon Pokagon, a chief of the Potawatomi tribe that once inhabited the area. Above the southern basin of Lake James, a large glacial lake in this moraine area, construction began on the Potawatomi Inn, which opened in 1927. Park personnel developed two beaches and over the next few years improved campgrounds at the north end of the park. The beginnings of a boys’ camp, built in part through a Civil Works Administration (CWA) project, appeared in the early 1930s on a bluff overlooking the upper basin of the lake. (CWA was a short-lived New Deal work program during the winter of 1933-34.)

CCC Company 556, initially formed in the fall of 1933 to do several projects, including an imaginatively designed group camp (all long since demolished) at Indiana Dunes State Park on Lake Michigan, finished its work there and established Camp SP-7 at Pokagon the following year. The park underwent an ambitious development program, including reforestation, landscaping, road building, and construction of numerous outdoor recreational facilities. The CCC boys hewed local timber and split native stone to construct buildings that harmonized especially well with the park environment, in keeping with guidelines created by the National Park Service, which oversaw master plans for CCC parks projects.  Perhaps the best example is the beautiful two-story shelterhouse (now called the “CCC Shelter”) that nestles at the edge of the woods above the beach. Nearly all the park’s present landscaping and buildings–including the old gatehouse, the saddle barn, the dining hall and much of the group camp, the bath house, and overnight cabins near the inn–are the work of the CCC, which remained in the park until January 1942. They also built a toboggan slide, which has since been rebuilt and remodeled several times, adding to winter fun at Pokagon. Other than several expansions of the Potawatomi Inn and the construction of a nature center in 1981, relatively little has been added or changed on the property. Most of Pokagon State Park, that encompassed by the boundary in place in 1942, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. I had the joyful task of writing that nomination in the mid-1990s at the behest of the CCC veterans, who presented me with a plaque upon the park’s successful listing.

Perhaps the best example is the beautiful two-story shelterhouse (now called the “CCC Shelter”) that nestles at the edge of the woods above the beach. Nearly all the park’s present landscaping and buildings–including the old gatehouse, the saddle barn, the dining hall and much of the group camp, the bath house, and overnight cabins near the inn–are the work of the CCC, which remained in the park until January 1942. They also built a toboggan slide, which has since been rebuilt and remodeled several times, adding to winter fun at Pokagon. Other than several expansions of the Potawatomi Inn and the construction of a nature center in 1981, relatively little has been added or changed on the property. Most of Pokagon State Park, that encompassed by the boundary in place in 1942, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. I had the joyful task of writing that nomination in the mid-1990s at the behest of the CCC veterans, who presented me with a plaque upon the park’s successful listing.

Initially I had met these men in 1991, when I was documenting all the New Deal sites and structures in Indiana’s state parks for the Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. As various structures built by New Deal agencies turned 50 years old, I frequently received calls from the preservation folks, asking about one building or another, and I had lobbied hard to do a survey and documentation like this. For this was not my first New Deal project; I had already put in ten years by then, starting with a grant from the Indiana Humanities Council for a year-long project, “Making a Better Indiana”: WPA, Labor and Leisure that sought out structures built by the New Deal and created programs around these findings. More grants followed, along with trips to the National Archives in those pre-computer days. Why WPA? Why the New Deal? In northern Indiana, where I grew up, I was surrounded with examples of their work. My favorites were Battell Park in Mishawaka, with its fieldstone fantasy rock garden that cascades down a bank of the St. Joseph River, and Washington Park in Michigan City, where the creative use of discarded construction material by FERA and WPA is still a wonder to behold, crowned with a four-story observation tower atop a dune.  What a joy it was to write that National Register nomination, one of my first, for the park and its zoo! For whatever reason, the New Deal captured my interest, and only later did I learn that a major engineering feat in South Bend, the straightening of an oxbow bend in the St. Joseph River, was a WPA project on which my grandfather had worked. And as I was busily collecting information on the New Deal in St. Joseph County, my mother casually mentioned that she had a clerical job at her high school through the National Youth Administration (NYA). Later I discovered several shelterhouses in various city parks around the state with plaques proudly proclaiming them to be the work of the NYA. The joy of discovery never ends–and I still stumble on New Deal work everywhere. Indiana was always a leading state in New Deal projects, difficult as that may be to believe given the current politics.

What a joy it was to write that National Register nomination, one of my first, for the park and its zoo! For whatever reason, the New Deal captured my interest, and only later did I learn that a major engineering feat in South Bend, the straightening of an oxbow bend in the St. Joseph River, was a WPA project on which my grandfather had worked. And as I was busily collecting information on the New Deal in St. Joseph County, my mother casually mentioned that she had a clerical job at her high school through the National Youth Administration (NYA). Later I discovered several shelterhouses in various city parks around the state with plaques proudly proclaiming them to be the work of the NYA. The joy of discovery never ends–and I still stumble on New Deal work everywhere. Indiana was always a leading state in New Deal projects, difficult as that may be to believe given the current politics.

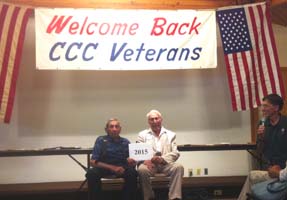

So, as always for the past 25 years, I spent the last Sunday of July at Pokagon State Park, honoring the boys of the Civilian Conservation Corps who, some 80 years ago, made the park what it is today. There were two veterans present (a third, bless him, had intended to come but had a fall and couldn’t make it).  Interpretive naturalist Fred Wooley, who retired this spring after 35 years, returned to emcee the program. Fred left a wonderful legacy himself; among other projects, his cherished dream of marking the location of every building on the site where the CCC camp was, including interpretive signage for each, has been realized.

Interpretive naturalist Fred Wooley, who retired this spring after 35 years, returned to emcee the program. Fred left a wonderful legacy himself; among other projects, his cherished dream of marking the location of every building on the site where the CCC camp was, including interpretive signage for each, has been realized.  And soon, the beautiful gatehouse built by these boys so long ago and abandoned owing to changing traffic patterns will become a mini museum dedicated to them. Their legacy lives on.

And soon, the beautiful gatehouse built by these boys so long ago and abandoned owing to changing traffic patterns will become a mini museum dedicated to them. Their legacy lives on.