On my way to somewhere else in Ohio, there was something I wanted to see again, an old tourist attraction in which my daddy had carried me around when I was a toddler, so my mom always told me. I have no memory of it; but indeed, a faded old photo survives from that visit to Ohio Caverns. I’d always had a yen to go back and actually see it. Now, since I later became an avid caver and knew something about karst, a geological landscape conducive to caves, I had assumed Ohio Caverns was in southern Ohio somewhere. But no, it turns out the cave is in a most unlikely location northeast of Dayton amidst rolling farmland. Fun with geology! Seeing that, I planned a route incorporating the old National Road (US40, mostly) into Ohio, then northeastward to Ohio Caverns and onward from there. Of course, the journey IS the way.

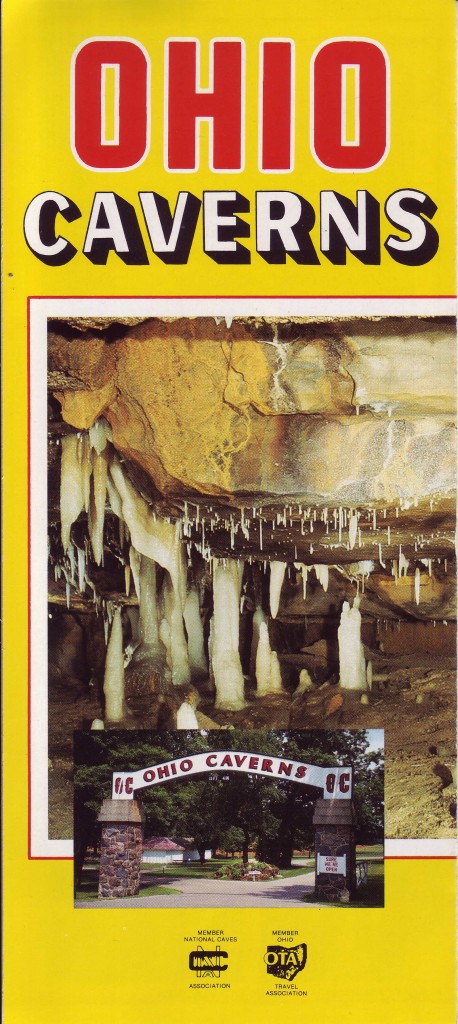

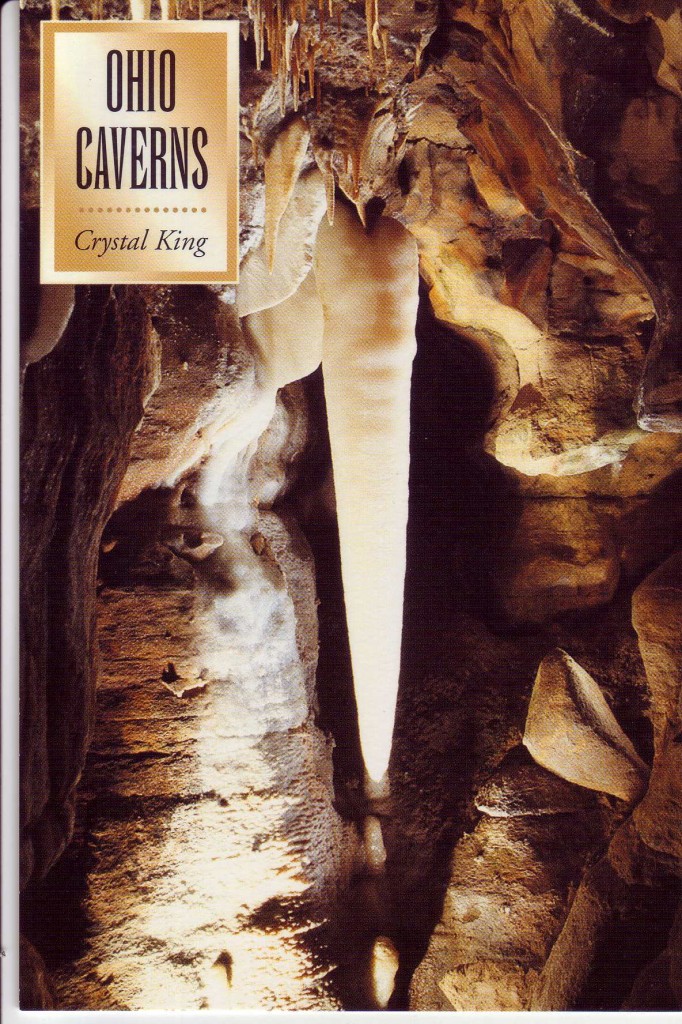

Ohio Caverns is one of those timeless attractions. The entrance to the property is essentially the same since it was erected in the 1930s; the cave, of course, has survived decades of tourists and is as mysteriously beautiful as ever. On a lovely fall day we were the only people there for a tour at that time, so we had the caverns to ourselves. Ah. It had been too many years since I’d been deep into a cave. The current entrance and passage through the caverns was created in 1925 and takes one through a fairyland (indeed, old brochures marketed the site as “Nature’s Fairyland.”), enhanced with direct and indirect lighting. Owing to a variety of mineral deposits, the Ohio Caverns are especially colorful. The guide pointed out a narrow passage off the main trail that had once been open to the public in the early twentieth century, shortly after the cave was discovered in 1897. Access to it was from the original opening, and with advance notice, one could arrange a tour. But this year (2012), the “historic tour” has been opened up and is offered regularly. I can never check places off my list; there is always a reason to return!

I was so taken with caves in my youth that after a visit to the granddaddy of them all, Mammoth Cave, I saw myself as a cave guide or some such. I produced an exhibit on cave geology for the school science fair and wrote a paper on the history of Mammoth Cave for my English class. But although I did not pursue a career in speleology, when I was in college I went on wild caving expeditions (also called “spelunking” by people who don’t actually do it), led by my geography professor, in whose earth science classes I excelled. What adventures we had! I continued for some years after to go caving in southern Indiana and even in the coral-based caves of Florida (painful for crawling!) But this does not make commercial caves any less appealing to me.

Caves have a long history as tourist destinations. Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, discovered in or before 1797 (although no doubt the natives of the region knew of it), within a few decades became one of the major scenic wonders of an American tour. Imagine the difficulty in traveling to such a forlorn location! But the famous Swedish soprano Jenny Lind (among other celebrities) came to visit in 1851, and supposedly gave an impromptu concert seated on a chair-like formation, known today as “Jenny Lind’s Armchair.” European visitors especially admired examples of America’s wild grandeur. Imagine, too, the differences in cave touring then and now. Guides led visitors by lantern or torchlight through passages that may or may not have been cleared of at least some of the rubble common to caves. (Of course, this is rather similar to what cavers experience in wild caves, only we probably do a lot more crawling and climbing and clambering through mud, using heavy duty flashlights and carbide lamps, than the tourists did.)

With the coming of the automobile, particularly the affordable Model T, droves of ordinary Americans took to the roads of their vast country to see the sights. Noting the profits made by the owners of Mammoth Cave (not yet a National Park), the poverty-stricken denizens of cave-pocked Kentucky saw the possibility of tourist dollars and scrambled amidst their rolling hills to find caves that could be exploited. The Kentucky cave wars of the 1920s sparked lies and misdeeds (travelers were led to to other caves by false signs, for instance), violence, and ultimately, a death in 1925, that of Floyd Collins, every caver’s bad example. He went off alone, telling no one where he was going (breaking two cardinal rules of caving), and became trapped underground in what later was named Sand Cave. He had been searching for a new cave or a new entrance to the Mammoth Cave system farther up the highway to snag tourists. Media circuses are nothing new–only the media have changed–so mobs of newspaper reporters and announcers for the newfangled radio came, as did the morbidly curious public, to cover what ultimately was the long, gruesome death of Collins from exposure and starvation. Would-be rescuers reached his body three days after he died. The remains were eventually buried on the Collins farm, but when his father sold the property a few years later, the new owner exhumed the body, placed it in a glass-topped coffin (no, I’m not making this up), and put it on display in Crystal Cave, which had been discovered by Collins some years earlier on the property. Even more disgusting is that the body was stolen, later to be recovered sans one leg! Still, the cave owners continued to display the body, the coffin now securely chained, until 1961, when the National Park Service (NPS) bought the property and closed the cave (now open to cave explorers with permission from NPS, no regular tours). Collins was finally laid to rest in a real cemetery in 1989, when NPS buried him in the Flint Ridge Cemetery. One suspects he might have wished to remain in the cave that he discovered. Some tourist materials refer to Crystal Cave as “Floyd Collins [sic] personal backyard cave.”

The cave wars and especially the death of Floyd Collins strengthened the growing movement to make Mammoth Cave a national park, which happened in the 1940s. Subsequent cave explorations have shown that most of the caves in this area are linked in one vast underground system. A connection between Mammoth Cave and the Flint Ridge caves was discovered in 1972, detailed in the book The Longest Cave by Roger W. Brucker and Richard A. Watson.

Too much drama! The Ohio Caverns, lacking such a grisly history, are as beautiful as any I have ever seen, with more formations packed within its confines than many larger caves. And the countryside surrounding it is so peaceful, with no hint of the beauties beneath it. I am eager to return to experience the “historic tour.” Besides, nearby West Liberty boasts other sites of interest, including the over-the-top Piatt Castles (http://www.piattcastles.org/piattcastles/Home.html), which have been open for tours for one hundred years (!) and, of course, Marie’s Candies (http://www.mariescandies.com/), a mere 56 years old, famous for its chocolates. I hear the road calling to me!

Cool brochures! Thanks for posting this. You keep the history of the place alive. It’s still here with us but it links us to what has been.