Some weeks ago I stumbled on the news that yet another building in South Bend listed in the National Register of Historic Places–this one was also a designated Local Landmark–was demolished. Someone had posted a video on a South Bend Facebook page of the destruction of the former South Bend Brewing Association taking place and it broke my heart. I had gone through a lot of trouble trying to save this building, crunching through dead pigeons and scaring up live ones on the top floor so I could reach and photograph the vat at the corner of the building–at the very top because brewing used a gravity process. A huge copper kettle was encased in the fourth floor tower that gave the structure its castle-like appearance.

In 1903 a group of mostly German, Polish, and Hungarian (then the three largest immigrant groups in South Bend) tavern owners formed the South Bend Brewing Association to manufacture and distribute beer. They built a large brick building on what was then called Michigan Avenue, later renamed Lincolnway when the Lincoln Highway was routed on it. Opened in 1905, the imposing structure housed a complete manufacturing facility. The process of brewing depended on gravity flow, and the building was a visual representation of the procedure. The chief products were Tiger Beer and Hoosier Beer. Immediately to the west, a bottling facility was built in 1910, later enlarged to accommodate the brewery’s offices.

Prohibition, effected in 1919 by the Volstead Act, forced the South Bend Brewing Association to change its line of manufacture. The renamed South Bend Beverage and Ice Association made non-alcoholic beverages (among them Hoosier Root Beer and Hoosier Sweet Cider), candy, ice cream, and in the non-food line, denatured alcohol for industrial purposes and ice. When Prohibition ended, the company resumed brewing beer for regional sales, producing around fifty thousand barrels yearly. After World War II business declined, at least in part because of a hefty federal excise tax on each barrel brewed that placed smaller breweries at a disadvantage. While the firm continued its ice manufacturing section, Polar Ice and Fuel, for a few additional years, the brewery closed in November 1950. Over time, various businesses used portions of the building: the White Way Glass Company in the 1950s; the I.W. Lower Company (paints) in the 1960s; a Harley-Davidson service and showroom facility in the 1970s and early 1980s. At the time I wrote the nomination in early 1999, a resale shop occupied the added-on storefront, and a glass manufacturer, Indiana Glass Company, used much of the first floor level. The rest was vacant. And now it’s gone.

I’m beginning to take this personally! South Bend’s other brewery, for which I also wrote the National Register nomination, is gone now, too, and its roots were much older with buildings to prove it. The multi-structure complex had started out as the family-run Muessel Brewery in 1852, and a couple of the buildings dated to the 1860s. German-born Christopher Muessel arrived in South Bend about 1852. His business soon outgrew its original location, so in 1865 Muessel purchased just over 136 acres of land northwest of town (west of what became Portage Avenue) and erected a larger complex of brick structures. His sons all assisted their father in the business; finally in 1893 the Muessel Brewing Company was incorporated, with patriarch Christopher Muessel as president. He died the following year at the age of 82, and his son Edward succeeded him, with other brothers and their sons all officers of the company. They brewed Standard and Bavarian beers and sold it in barrels to taverns; they bottled Arzburg Export for home consumption. Expansion of the plant followed incorporation, including a new bottling house; an attractive new brick office building was constructed right after the turn of the century that soon sat in the shadow of a mammoth brewing building to the west, constructed in 1911. It was in that particular building that I nearly got killed in my efforts to document it; a wall on one side had been knocked down in order to salvage the huge copper vats on the third floor level, leaving massive round openings in the floor and the interior open to the weather. It was winter and the floors were a veritable skating rink. I nearly slid into the black void where once a vat had been.

During Prohibition, Muessel briefly attempted to keep going by producing non-alcoholic beverages but was forced to close about 1922. Before the plant reopened after the repeal of Prohibition, the company enlarged the facilities and constructed a new bottling plant east of the office building. But the Muessel Brewing Company faltered, and following an announcement to their stockholders in 1936, they reorganized and became a significant part of Drewry’s, Limited, a Canadian company that had just begun distribution in the United States. Drewry’s was Canada’s first brewing company, started in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1877. Its newly acquired South Bend plant became its first in the United States, headquarters for nationwide distribution as well as manufacture. The company indicated that major ingredients used in this plant were to be purchased mostly in the United States, all news which surely boded well for the region gripped by the Great Depression. Drewry’s also announced that the plant would be completely unionized; there was “a spirit of good fellowship and cooperation in South Bend.” Since this was to be the center for nationwide distribution, the plant was yet further remodeled and enlarged, adding more truck terminals and case storage facilities as needs required. Among the Drewry’s brands (besides Drewry’s itself) produced were Pfeiffer, Schmitt, and Old Dutch. Drewry’s later merged with Associated Brewing Company out of Detroit, but continued to keep its own identity and its ties with South Bend.

But in 1972, Associated sold Drewry’s to the G. Heileman Brewing Company of LaCrosse, Wisconsin. The new owner chose to phase out the South Bend plant, and brewing ceased in the fall of that year. After 120 years, the city no longer had a local brewery. There were efforts to maintain local distributorship of Drewry’s beer, but not unexpectedly, there was a great deal of local backlash against the product. A few years after the brewery closed, a new owner acquired the site and named it “Omniplex,” a startup facility for small businesses. At the time of my work on the National Register nomination, the complex was less than half occupied with various enterprises. Evidently, no one cared when the complex was listed; indeed, it seemed to be largely unknown, even though the work was commissioned by the city’s Historic Preservation Commission! In 2017, the majority of the complex was demolished to great fanfare; those that remain are scheduled to be torn down this fall, again, sadly, a matter of celebration to the neighborhood.

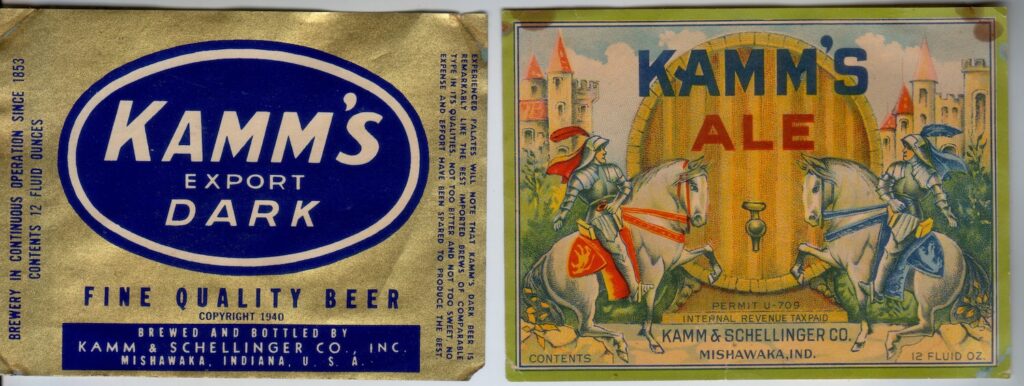

Now only one of the triumvirate of local breweries in South Bend-Mishawaka remains standing (abandoned), but for how long? This one also had origins in the 1850s, in a small operation begun in Mishawaka by a man named Wagner. Adolph Kamm, along with some partners, purchased the brewery in 1870; in the 1880s, Kamm’s brother-in-law Nicholas Schellinger became a partner and it was incorporated as Kamm & Schellinger Brewing Company. It closed in 1951 but had a second life, opening in 1968 as a festival marketplace called the 100 Center. That languished in the 1980s.

Today this mostly intact brewery complex of several substantial brick structures along the St. Joseph River is greatly endangered, despite its listing in the National Register–that will not save it! But Indiana Landmarks placed it on its Ten Most Endangered List, which has a really good track record of saving historic buildings as the bulldozers approach. There is hope. But the lesson here is that placing historic buildings in the National Register is not enough. We must keep watch and keep working!

Poor GJ. You struggle so hard, I know it has to hurt when this happens. Just know, there are bunches of us out here who do greatly appreciate what you do to preserve that which will never be again.

Thanks

Thank you, Al. It does hurt. I never dreamed when I started working in preservation so long ago that it would still be so hard.

But still we must try.