Collier Lodge

I first learned of Collier Lodge, originally built deep in the Kankakee Marsh along the river of that name, back in the 1990s at a historic preservation conference in South Bend. A fellow from Porter County gave a presentation about the significance of this battered structure that once hosted the likes of Teddy Roosevelt and author Lew Wallace. I recall talking to him about writing a nomination to the National Register of Historic Places, but he said they would be handling that themselves. Great!

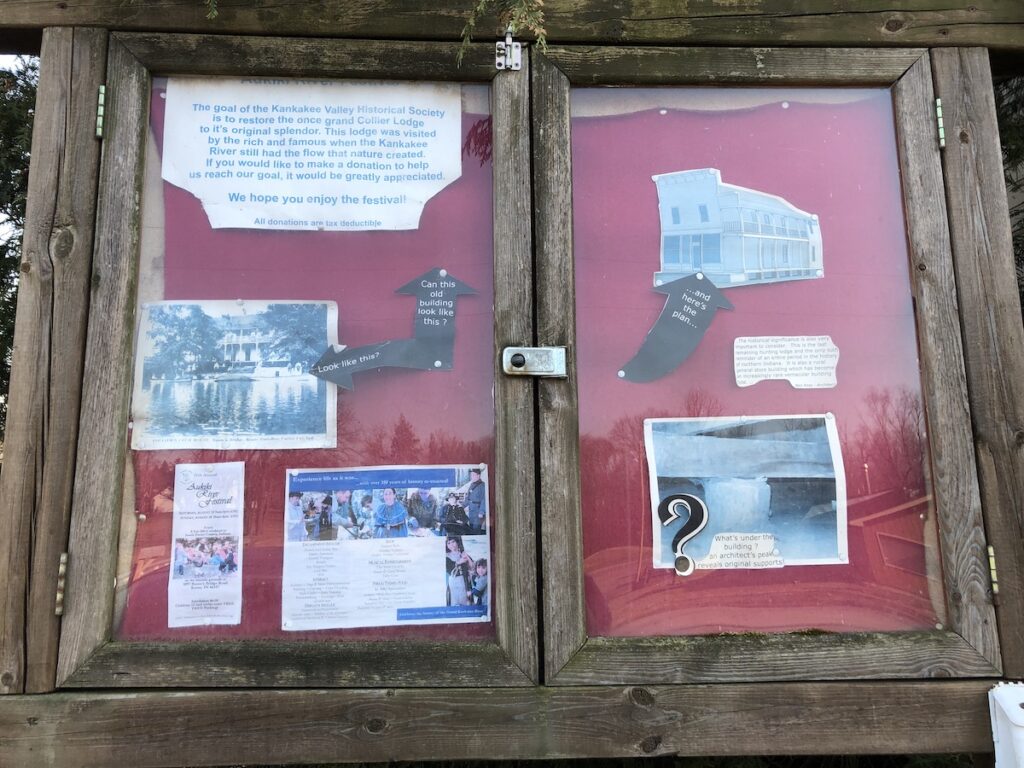

A few years later I was in the general vicinity and drove over to take a peek. The surrounding ground had been cleaned out a good bit, the building painted and presumably stabilized–some funding had been obtained for the purpose–and hopeful signage erected on and in front of the building about restoring the lodge. All right then! Naturally, I long assumed that it had happened. Even folks who were working at Indiana Landmarks (the statewide non-profit preservation organization) at the time, helping in the early stages, assumed it had ultimately been restored. I suppose it’s just that this place is so out of the way. I had been intending for years to get back there to see it (in its gloriously restored state, I had thought) and only managed to hurry up there last week when I learned of its imminent demolition.

This site is really important historically. The sloggy marsh immediately south of the building is actually the original main channel of the river, before it was dredged and straightened and turned into essentially a canal in the decade before World War I. Here had been one of the only places travelers could get through the swamp relatively easily. The vast Kankakee Marsh was formidable indeed, later becoming known as the “Everglades of the North.” Its presence was why Indiana’s first border-to-border “highway” in the 1830s, the Michigan Road, took a severe northeast jog from Logansport up to South Bend then west over to Michigan City. But some preferred the more direct route through the swamps, and here there was a ford, known, in a variety of spellings, as Potawatomi Ford, indicative of the fact that there were certainly native Americans in the region. The first settler of European ancestry here seems to have been George Eaton, who operated a ferry for several years, interrupted only briefly by the construction of a bridge, which soon burned. After Eaton’s death in 1851, his widow continued running the ferry until her death six years later. The ferry continued until one Enos Baum built a more substantial toll bridge at the site of the ford, giving the local community its name of Baum’s Bridge that continues to this day. (It’s on Indiana maps.) The Kankakee Marsh, however, was a wild and difficult place to live, although a number of people fed their families and even made a good living from the fruits of fishing, hunting, and trapping, perhaps with a small subsistence farm on the side. The quantities of fish and game are what began to draw wealthy sportsmen (indeed, only men at first) to come play pioneer and spend a week or much longer camping and hunting. The area was so vast and rich, there seemed little danger of the attractions running out. Soon any number of clubhouses appeared, constructed by sportsmen’s groups from as far away as Pittsburgh. Many of them clustered about Baum’s Bridge. Some individuals built private lodges; Lew Wallace lived for weeks at a time on a houseboat anchored near the bridge. In the 1890s Elwood and Flora Collier built a large house above the river to house themselves and their three children, intending to establish some sort of business there. Mr. Baum built a houseboat to take his family to the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1903 (and made it), then used it for an excursion boat venture, which failed because the river’s depth was unpredictable. Undaunted, the family remodeled their house into an inn and named it Collier Lodge. Upstairs were accommodations, while the first floor contained a restaurant and store that catered to hunters and the growing number of tourists. The chicken and fish dinners on Sundays were legendary, enjoyed by locals as well as visitors.

In the eyes of developers, all that good land under the waters of the great swamp taking up parts of six counties should not go to waste, and so in the decade leading up to World War I, the area was ditched and drained and the river straightened. The game was soon gone, scattered to the four winds or killed off. So ended an era, and over time, all the clubhouses and lodges disappeared–all but one, though it stood abandoned for decades.

How wonderful that Collier Lodge was rediscovered! It could be a wonderful meeting place, retreat, with a small museum, perhaps–and this just as early efforts to restore part of the Great Kankakee Marsh were beginning. The property was purchased and the newly formed (2001) Kankakee Valley Historical Society took ownership. I regularly heard of the annual Aukiki River Festival held in summer as a fun and informative event, intended to raise awareness and funds. The archaeology department of Notre Dame conducted a dig the following year, expecting to find artifacts from the hunting lodge days, perhaps some pioneer relics, and maybe some native American remnants if they were lucky. Little did they realize how rich and deeply layered the site would prove to be. The finds ranged from buttons and camping items from the late 19th century to projectile points and other stone tools from the Early Archaic period (ca.9000 BCE)! Annual digs have continued into the present, with another scheduled for this summer. Artifacts from several successive native cultures, the remains of a pioneer cabin, and much more have been excavated and catalogued, adding a wealth of information on several thousand years of human activity in the Great Kankakee Marsh. So exciting! And yet, the largest artifact of all, the Collier Lodge–the very reason all this research began, the last extant building of an important era of history–was put aside until it was deemed too far gone to save. (In my experience, it probably still could be saved, but the expense is so much greater now.) Now it seems there is a plan to build a replica in another location. The actual building would have been grandfathered in, in place, even though it is on a flood plain.

A replica, IF it ever happens, is meaningless on a different site. Preservation gone wrong. As a local woman who came by as I was photographing the lodge said, “It’s a shame.”